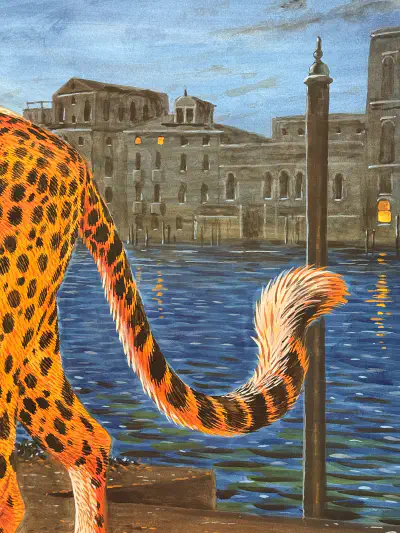

Tutto is [Ford’s] first body of work to focus on a single individual: the eccentric Milanese heiress Luisa Casati (1881–1957). Depicting the exotic animals that she kept, Ford portrays her years in Venice shortly before World War I.

Known as La Marchesa, Casati was one of Europe’s wealthiest women and is legendary for her extravagant pursuit of aesthetic extremes and social recognition. Startled onlookers describe how she wore snakes as necklaces, walked with a pair of cheetahs in Venice’s piazzas, and attended an opera clad in a headdress of peacock feathers that were stained with the blood of a freshly killed chicken.